This Directive emphasises that the determination of ‘equal work’ requires objective criteria and should be based on weighted factors that are relevant and justified for the organisation concerned.

During my participation at the recent WorldatWork's Total Rewards conference in Orlando in May 2025, I observed that many American organisations’ job architectures still rely on simpler, non-analytical job classification methods. This aligns with findings from the "Job Evaluation and Market Pricing Practices Survey" conducted in collaboration of gradar and WorldatWork in 2020 that showed 80% of participants using benchmarking as their main method of job evaluation. Such non-analytical methods are frequently employed for levelling jobs within compensation surveys or broader job architectures, owing primarily to their perceived simplicity and ease of implementation.

Work of equal value

However, the critical question arises: Can non-analytical job classification genuinely assess "work of equal value" accurately and reliably?

Analytical job evaluation, specifically point-factor based, systematically breaks down jobs into their constituent components such as skills, effort, responsibility, and working conditions.

These criteria, initially established by the International Labour Organisation’s influential Geneva scheme from the 1950s and subsequently reinforced in their comprehensive guide on Gender-Neutral Job Evaluation (2009), ensure that each factor is assessed and scored objectively, enabling detailed and transparent comparisons across all jobs within an organisation. The European Commission's staff working document SWD(2013) 512 explicitly endorses such analytical methods, recognizing their potential for reducing discriminatory practices and thus being "most appropriate for job evaluation in a gender equality context."

Legal precedent

This aligns with EU legal precedents such as:

- Summary: The Defrenne II case is a landmark decision by the European Court of Justice (ECJ) that established the principle of equal pay for men and women for equal work or work of equal value. The case involved Gabrielle Defrenne, a Belgian airline stewardess, who was paid less than her male colleagues. The ECJ ruled that the principle of equal pay is directly effective, meaning it can be invoked by individuals in national courts. This decision was pivotal in advancing gender equality in employment across the European Union.

- Summary: The Gisela Rummler case is a significant decision by the European Court of Justice (ECJ) that addressed the use of physical effort and muscular demand as criteria in job classification systems for determining pay rates. The case involved Gisela Rummler, an employee at a German printing firm, who sought reclassification to a higher pay grade. The ECJ ruled that job classification systems can include criteria such as muscular effort or the heaviness of work, provided that these criteria are objectively justified by the nature of the tasks and do not result in discrimination based on sex. The Court emphasized that such systems must be based on criteria that apply equally to both men and women and must not systematically disadvantage one sex. The decision clarified that while physical effort can be a factor in job classification, it must be part of a broader system that considers various criteria to ensure non-discrimination.

- Summary: The Danfoss case highlighted the shift in the burden of proof in equal pay cases where there is a lack of transparency. The European Court of Justice ruled that if an employer does not provide transparent information about pay structures, the burden of proof shifts to the employer to show that there is no discrimination. This decision underscores the importance of transparency in pay systems to ensure equal pay for work of equal value.

- Summary: The Kutz-Bauer case reinforced the requirement for gender-neutral job evaluations. The European Court of Justice ruled that job evaluation systems must be free from gender bias to ensure equal pay for work of equal value. The case involved a German social worker, Monika Kutz-Bauer, who argued that her job was undervalued compared to male-dominated roles. The court confirmed that job evaluation methods must be objective and non-discriminatory, ensuring that jobs traditionally held by women are not systematically undervalued.

- Summary: The Brunnhofer case is a significant decision by the European Court of Justice (ECJ) that clarified the application of the principle of equal pay for men and women for equal work or work of equal value. The case involved Mrs. Brunnhofer, an employee at an Austrian bank, who received a lower monthly allowance than a male colleague in the same job classification. The ECJ ruled on the burden of proof in equal pay cases, stating that it is primarily the responsibility of the employee to prove pay discrimination. Once established, the burden shifts to the employer to justify any pay differences with objective, non-discriminatory factors. The Court also emphasised that classification in the same job group under a collective agreement is not sufficient alone to establish equal work or work of equal value. This decision reinforced the importance of objective criteria and transparency in pay structures to ensure gender equality in employment.

- Summary: The Tesco Stores case extended the principle of "work of equal value" comparisons across different sites and employers. The European Court of Justice ruled that employees can compare their pay with colleagues in different locations or roles within the same organisation if there is a "single source" responsible for pay conditions. This decision allows predominantly female shop floor workers to compare their pay with predominantly male distribution centre workers, potentially leading to significant back pay claims for equal work of equal value.

These cases collectively represent some significant milestones in the development of equal pay legislation and gender equality in the workplace within the European Union.

On the other hand, non-analytical methods categorise jobs broadly into predefined classes based on job descriptions and subjective assessments, often influenced by traditional job roles and gender biases. These classifications, i.e. Technicians vs. Business Support, can unintentionally perpetuate undervaluation, particularly of female-dominated roles.

European and British jurisprudence underscores the risks associated with non-transparent and subjective methodologies. Given this context, relying solely on non-analytical methods could expose organisations to legal and reputational risks, particularly under the intensified scrutiny of the EU Pay Transparency Directive.

Where do we go from here?

Given the lack of regulatory details, significant concerns exist regarding clarity and legal certainty in defining equal or equivalent work. The current definition merely reflects the European Court of Justice (EuGH) jurisprudence, which may evolve, causing ongoing legal uncertainty for both employers and employees. Specifically for Germany, the existing assumption regarding the adequacy of collective bargaining agreements under the current German Entgelttransparenzgesetz remains inadequately clear. A more explicit presumption that collective bargaining agreements inherently comply with gender equity standards would reduce ambiguity and subsequent litigation risks, provided that these agreements genuinely assess work of equal value and do not merely reflect individual pay preferences through personalised classification.

Practical implementation challenges

Implementing analytical job evaluation methods can indeed pose practical hurdles. Analysing each individual position for work of equal value is rarely feasible or economically viable, necessitating a consolidation of positions into broader "jobs" within a coherent job architecture. This enables the job's evaluation outcome, such as its assigned job family and grade, to be inherited by position holders, whose pay is then locally determined through market benchmarks (commonly seen in the American context) or pay bands (typical in European contexts).

Grading templates

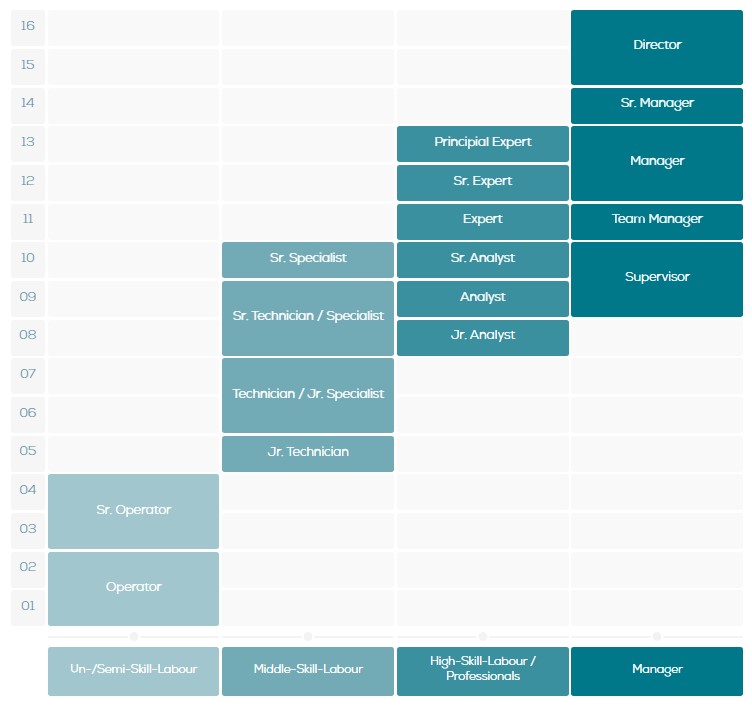

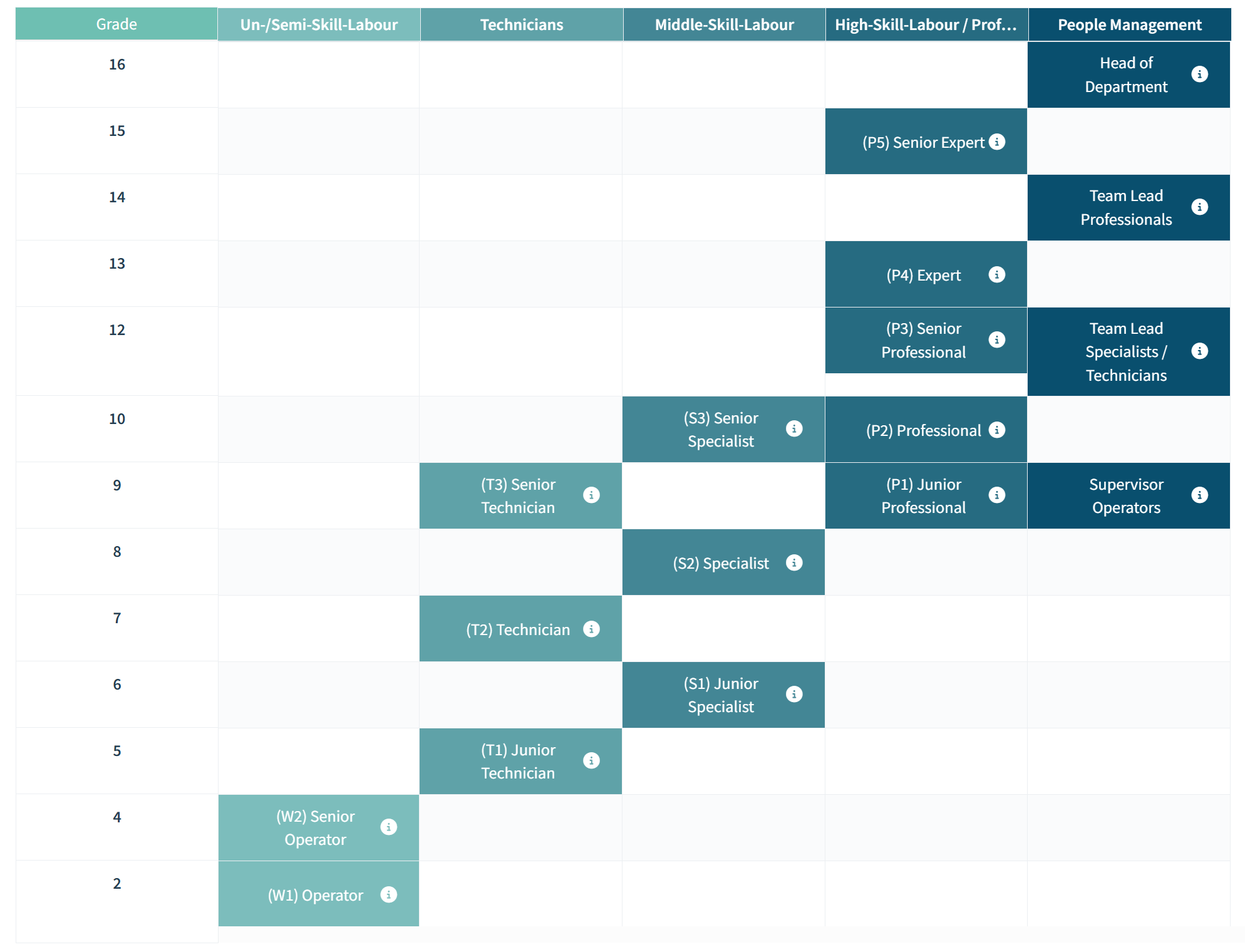

Figure 1 This is a screenshot of gradar's fully customisable grading templates, which enable a hybrid approach with analytically founded job classifications.

While acknowledging the practical need for rapid job evaluations, as often facilitated by capsule-level job descriptions (P1 / P2 / P3 / …) in traditional non-analytical job classifications, a hybrid approach might present a balanced solution. In this model, initial job levels would be analytically grounded, providing a solid foundational standard. Subsequently, this would allow controlled deviations on a case-by-case, job-by-job, basis, enabling rapid initial levelling while still upholding the principles of transparency and objective comparability.

It is important to recognize that legislators may not always fully grasp the EU’s intent behind these detailed requirements. Consequently, the task of determining whether specific jobs are indeed of "equal value" will likely fall to the courts. This further reinforces the necessity for transparent and objective evaluation methodologies, as judicial bodies will be tasked with interpreting these standards and applying them in practical cases.

Conclusively, analytical, point-factor-based evaluation not only ensures compliance with evolving legal frameworks but also offers a robust, transparent framework for genuinely assessing "work of equal value." While non-analytical methods might initially appear simpler, the increased transparency and fairness inherent in analytical methods represent a prudent long-term strategic investment for organisations committed to fairness, equity, and compliance.

Benefits beyond compliance

Adopting an analytical job evaluation system such as gradar brings strategic value well beyond mere regulatory compliance. Such a structured framework provides organisations with:

- Clear linkages to salary benchmarks and compensation structures, improving external competitiveness and internal equity.

- Enhanced talent management integration, where job descriptions, required competencies, and specific skill sets are explicitly aligned to detailed job profiles.

- Improved governance and administration, streamlining management oversight by consolidating job structures and significantly reducing the administrative burden associated with fragmented job classification systems.

- Focused talent insights, allowing HR leaders and management to better understand talent requirements and drive targeted strategies around talent acquisition, development, and retention.

- Heightened employee engagement and internal mobility, achieved by transparently clarifying career paths, enabling consistent succession planning, and encouraging cross-functional talent mobility.

A clearly defined job architecture not only resolves traditional job classification challenges but also serves as a strategic foundation for all core talent management processes, from compensation to career development and performance management, thus deeply embedding fairness, clarity, and organisational effectiveness into everyday HR operations.

Employee and stakeholder engagement

Active employee and stakeholder involvement is critical when implementing analytical job evaluation methods, a point strongly emphasised in the ILO’s guidelines on gender-neutral job evaluation. Such engagement is essential for ensuring transparency, fairness, and broad acceptance of the outcomes. The EU Pay Transparency Directive explicitly underscores the importance of involving employee representatives to enhance credibility and acceptance of pay transparency measures.

Organisations benefit significantly when employees and stakeholders actively participate in the design, validation, and ongoing management of job evaluation systems. Engaging stakeholders early and continuously facilitates smoother change management and promotes a culture of shared ownership and mutual accountability, ultimately strengthening trust and acceptance of the evaluation results.

In summary, carefully addressing practical challenges, clearly communicating broader organisational benefits, and proactively engaging stakeholders significantly enhance the successful implementation and sustainability of analytical, point-factor-based job evaluation methods.